Ever since I started getting closer to machine learning, well before I started my PhD, I have always found it extremely annoying to keep track of experiments, parameters, and minor variations of code that may or may not be of utmost importance to the success of your project.

This gets incredibly uglier as you wander into uncharted territory, when best practices start to fail you (or have never been defined at all) and the amount of details to keep in mind becomes quickly overwhelming.

However, nothing increases the entropy of a project like introducing new people into the equation, each one with a different skillset, coding style, and amount of experience.

In this post I’ll try to sum up some of the problems that I have encountered when doing ML projects in teams (both for research and competitions), and some of the things that have helped me make my life easier when working on a ML project in general.

Some of these require people to drop their ancient, stone-engraved practices and beliefs: they will hate you for enforcing change, but after a while you’ll all be laughing back at when Bob used to store 40GB of .csv datasets on a Telegram chat.

The three main areas that I’ll cover are:

- How to deal with code, so that anyone will be able to reproduce the stuff you did and understand what you did by looking at the code;

- How to deal with data, so that good ol’ Bob will not only stop using Telegram as a storage server, but will also stop storing data in that obscure standard from 1997;

- How to deal with logs, so that every piece of information needed to replicate an experiment will be stored somewhere, and you won’t need to run a mental Git tree to remember every little change that the project underwent in the previous 6 months.

Code

In this post I’ll be mostly talking about Python.

That’s because 99% of the ML projects I’ve worked on have been in Python, and the remaining 1% is what Rule 1 of this section is about. I’ll try to keep it as general as possible, but in the end I’m a simple ML PhD student who goes with the trend, so Python it is.

Let’s start from two basic rules (which, I assure you, have been made necessary by experience):

1. Use a single programming language

Your team members may come from different backgrounds, have different skills, and different degrees of experience. This can become particularly problematic when coding for a project, as people will try to stick to the languages they know best (usually the ones they used during their education) because they rightfully feel that their performance may suffer from using a different language.

Democratically deciding on which language to use may be a hard task, but you must never be tempted to tolerate a mixed codebase if you are serious about being a team.

Eventually, someone might have to put their fist down and resort to threat: don’t push that .r file on my Python repo ever again if you wish to live.

2. Everybody must be using the same version of everything

This should be pretty obvious, but I’ve witnessed precious hours being thrown to the wind because OpenAI’s gym (just to name one) was changed in the backend between versions and nobody had a clue why the algorithms were running differently on different machines.

Another undesirable situation may present itself when integrating existing codebases written in different versions of the same language. This is obviously more relevant with Python 2/3, where the code is backwards compatible enough between versions for the integration to go smoothly, but 2/3 is sneakily equal to 0 in Python 2 and 0.66 in Python 3 (and this may not always be apparent immediately).

To make it short:

- check your Pythons.

pip install -Uat least once a week (or never at all until you’re done).

Going a bit more in depth into the realm of crap that one may find oneself in, even once you’re sure that everyone is synced on the basics, there are some additional rules that can greatly improve the overall project experience and will prepare you for more advanced situations in any team project.

3. Write documentation for at least input and output

You have to work with the sacred knowledge that people may not want to read your code.

Good documentation is the obvious way to avoid most issues when it comes to working on a team project, but codebases tend to get really big and deadlines tend to get really close, so it may not always be possible to spend time documenting in detail every function.

A simple trade-off for the sake of sanity is to limit documentation to a single sentence describing what functions do, but clearly describing what are the expected input and output formats. A big plus here is to perform runtime checks, and fail early when the inputs are wrong.

For instance, one could do something like this:

def foo(a, b=None):

""" Does a thing.

:param a: np.ndarray of shape (n_samples, n_channels); the data to be processed.

:param b: None or int; the amount of this in that (if None, it will be inferred).

:return: np.ndarray of shape (n_samples, n_channels + b); the result.

"""

if a.ndim != 2:

raise ValueError('Expected rank 2 array, got rank {}'.format(a.ndim))

if b is not None and not isinstance(b, int):

raise TypeError('b should be int or None')

4. git branch && git gud

This is actually a good general practice that should be applied in any coding project.

Do not test stuff on master, learn to use the tools of the trade, and read the Git cheat-sheet.

Do not be afraid to create a branch to test a small idea (fortunately they come cheap), and your teammates will appreciate you for not messing up the codebase.

5. Stick to one programming paradigm and style

This may be the hardest rule of all, especially because it’s fairly generic.

It’s difficult to formalize this rule properly, so here are some examples:

- write PEP8 compliant code (or the PEP8 equivalent for other languages);

- don’t use single letters for variables that have a specific semantic meaning (e.g. don’t use

Wwhen you can useweights); - keep function signatures coherent;

- don’t write cryptic one-liners to show off your power level;

- don’t use a

forcycle if everything else is vectorized; - don’t define classes if everything else is done with functions in modules (e.g. don’t create a

Loggerclass that exposes alog()method, but create alogging.pymodule andimport logfrom it); - don’t use sparse matrices if everything else is dense (unless absolutely necessary, and always remember Rule 3 anyway).

I realize this is all a bit vague, so I’ll just summarize it as “stick to the plan” and shamelessly leave you to learn from experience.

6. Don’t add a dependency if you’ll only use it once

This could have actually been an example of Rule 5, but I’ve seen too many atrocities in this regard to not make it into a rule.

Sometimes it will be absolutely tempting to use a library with which you have experience to do a single task, and you will want to import that library “just this once” to get done with it.

This quickly leads to dependency hell and puts Rule 2 in danger, so try to avoid it at all costs.

Examples of this include using Pandas because you are not confident enough with Numpy’s slicing, or importing Seaborn because Matplotlib will require some grinding, or copy-pasting that two-LOC solution from StackOverflow.

Of course, this is gray territory and you should proceed with common sense: sometimes it’s really useless to reinvent the wheel, in which case you can import away without guilt, but most times a quick Google search will provide you with native solutions within the existing requirements of the project.

7. Comment non-trivial code, but do not over-commit to the cause

Comments should be a central element of any codebase, because they are the most effective way of allowing others (especially the less skilled) to understand what you did; they are the only ones that can save your code’s understandability should Rule 5 come less.

Especially in ML projects, where complex ideas may lead to complex architectures, and most stuff is usually vectorized (i.e. ugly, ugly code may happen more frequently than not), leaving a good trail of comments behind you may be crucial for the sake of the project, especially when you find yourself debugging a piece of code that was written six months before.

At the same time, you should avoid commenting every single line of code that you write, in order to keep the code as tidy as possible, reduce redundancy, and improve readability.

So for instance, a good comment would be:

output = np.dot(weights, inputs) + b # Compute the model's output as WX + b

where the information conveyed is as minimal and as exact as possible (maybe this specific example shouldn’t even require a comment, but you get the idea). Note that in this case the comment refers to variables by other names: this is not necessarily a good practice, but I find it helpful to link what you are doing in the code with what you did in the associated paper.

On the other hand, a comment like the following (actually found in the wild):

# Set the model's flag to freeze the weights and prevent training

model.trainable = False

should be avoided at all costs. But you knew that already.

Data

Data management is a field that is so vast and so complex that it’s basically impossible for laymen (such as myself) to do a comprehensive review of the best practices and tools.

Here I’ll try to give a few pointers that are available to anyone with basic command line and programming knowledge, as well as some low-hassle tricks to simplify the life of the team.

You should probably note, as a disclaimer, that I’ve never worked with anything bigger than 50GB, so there’s that. But anyway, here we go.

1. Standardize and modernize data formats

Yes, I know. I know that in 1995, IEEE published an extremely well defined standard to encode an incredibly specific type of information, and that this is exactly the type of data that we’re using right now.

And I know that XML was the semantic language of the future, in 2004.

I know that you searched the entire Internet for that dataset, and that the Internet only gave you a .mat file in return.

But, this is what we should do instead:

- use

.npzfor matrices; - use

.jsonfor structured data; - use

.csvfor classic relational data (e.g. the Iris dataset, stuff with well defined categories); - serialize everything else with libraries like Pickle or H5py.

Keep it as simple, as standard, and as modern as possible.

And remember: it’s better to convert data once, and then read from the chosen standard format, rather than converting at runtime, every time.

2. Drop the Dropbox

Dropbox and Google Drive are consumer-oriented platforms that are specifically designed to help the average user have a simple and effective experience with cloud storage. They surely can be used as backend for more technical situations through the use of command line, but in the end they will bring you down to hell and keep you there forever.

Here’s a short list of tools and tips for cloud storage and data handling that I have used in the past as alternative to the big D (no pun intended).

Data storage:

- Set up a centralized server (as you most likely do anyway to run heavy computations) and keep everything there;

- Set up and S3 bucket and add a

dataset_downloader.pyto your code; - Set up a NAS (good for offices, less for remote development);

Data transfers:

- Use the amazing transfer.sh, a free service that allows you to upload and download files up to 10GB for up to 30 days;

- Use

rsync; - Use

sftp; - Use Filezilla or equivalent

sftpclients.

3. Don’t use Git to move source files between machines

This is once again an extension of the previous rule.

The situation is the following: you’re debugging a script, testing out hyperparameters, or developing a new feature of your architecture. You need to run the microscopically different script on the department’s server, because your laptop can’t deal with it. You git commit -m 'fix' && git push origin master. Linus Torvalds dies (and also you broke Rule 4 of the coding section).

Quick fix: keep a sftp session open and put the script, instead. Once you’re sure that the code works, then you can roll back the changes on the remote machine, commit from the local machine just once, and then pull on the remote to finish.

This will make life easier for someone who has to roll back the code or browse commits for any other reason, because they won’t have to guess which one of the ten ‘fix’ commits is the right one.

4. Don’t push data to Github

On a similar note, avoid using Github to keep track of your data, especially if the data is subject to frequent changes. Github will block you if you surpass a certain file size, but in general this is a solution that doesn’t scale.

There is one exception to this rule: small, public benchmark datasets. Those are fine and may help people to reproduce your work by conveniently providing them with a working OOB environment, but everything else should be handled properly.

5. Test small, run big

Keep a small subset of your data on your development machine, big enough to cover all possible use cases (e.g. train/test splits or cross validation), but small enough to keep your runtimes in the order of seconds.

Once you’re ready to run experiments for good, you can use the whole dataset and leave the machine to do its work.

Experiments

Experiment, runs, call them however you like. It’s the act of taking a piece of code that implements a learning algorithm, throw data at it, get information in return.

I’ve wasted long hours trying to come up with the perfect Excel sheet to keep track of every nuance of my experiments, only to realize that it’s basically impossible to do so effectively.

In the end, I’ve found that the best solutions are to either have your script output a dedicated folder for each run, or have an old school paper notebook on which you record your methodology as you would take notes in class. Since the latter is more time consuming and personal, I’ll focus on the former.

1. Keep hyperparameters together and logged

By my very own, extremely informal definition, hyperparameters are those things that you have to pick by hand (or cross-validation) and that will FUCK! YOU! UP! whenever they feel like it. You might think that the success of your paper depends on your hard work, but it really doesn’t: it’s how you pick hyperparameters.

But asides aside, you really should keep track of the hyperparameters for every experiment that you run, for two simple reasons:

- They will be there when you need to replicate results or publish your code with the best defaults;

- They will be there when you need to write the Experiments section of the paper, so you will be sure that result A corresponds to hyperparameters set B, without having to rely on your source code to keep track of hyperparameters for you.

In general, it’s also a good idea to log every possible choice and assumption that you have to make for an experiment, and that includes also meta-information like what optimization algorithm or loss you used in the run.

By logging everything properly, you’ll ensure that every team member will know where to look for information, ad they will not need to assume anything else other than what is written in the logs.

A cool code snippet that I like to run after the prologue of every script is the following (taken from my current project):

# Defined somewhere at some point

def log(string, print_string=True):

global LOGFILE

string = str(string)

if not string.endswith('\n'):

string += '\n'

if print_string:

print(string)

if LOGFILE:

with open(LOGFILE, 'a') as f:

f.write(string)

# Define all hyperparameters here

# ...

# Log hyperparameters

log(__file__)

vars_to_log = ['learning_rate', 'epochs', 'batch_size', 'optimizer', 'loss']

log(''.join('- {}: {}\n'.format(v, str(eval(v))) for v in vars_to_log))

which will give you a neat and tidy:

/path/to/file/run.py

- learning_rate: 1e-3

- epochs: 100

- batch_size: 32

- optimizer: 'adam'

- loss: 'binary_crossentropy'

2. Log architectural details

This one is an extension of Rule 1, but I just wanted to show off this extremely useful function to convert a Keras model to a string:

def model_to_str(model):

def to_str(line):

model_to_str.output += str(line) + '\n'

model_to_str.output = ''

model.summary(print_fn=lambda x: to_str(x))

return model_to_str.output

Keep track of how your model is structured, and save this information for every experiment so that you will be able to remember changes in time.

Sometimes, I’ve seen people copy-pasting entire scripts in the output folder of an experiment in order to remember what architecture they used: don’t.

3. Plots before logs

We do science to show our findings to the world, the other members of our team, or at the very least to our bosses and supervisors.

This means that the best results that you may obtain in a project instantly lose their value if you cannot communicate properly what you found, and in 2018 that means that you have to learn how to use data visualization techniques.

Books have been written on the subject, so I won’t go into details here.

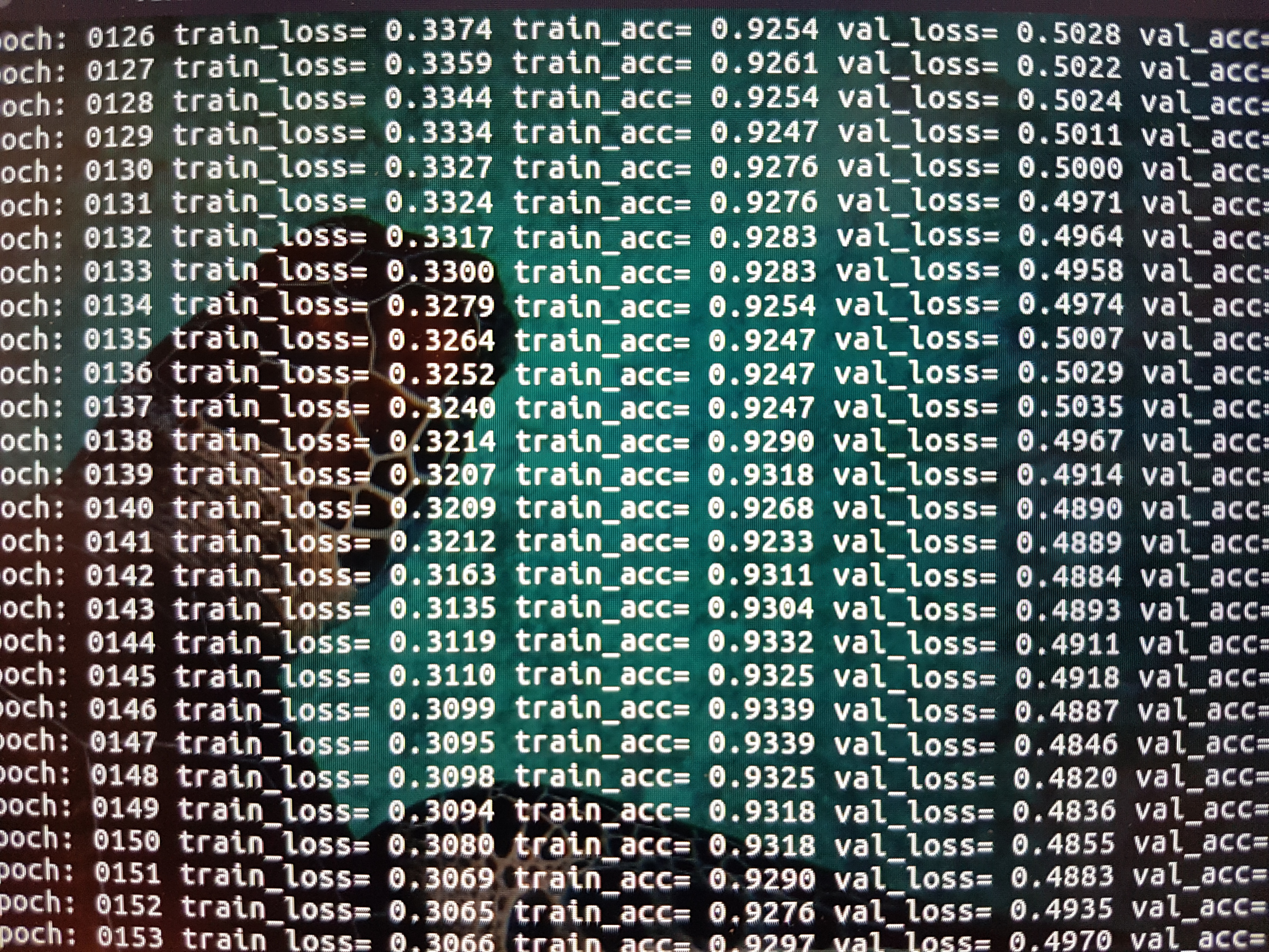

Just remember that a good visualization always trumps a series of unfriendly floats floating around.

Some general tips on how to do data viz:

- label your axes;

- don’t be scared of 3D plots;

- time is a powerful dimension that should always be taken into consideration: create animated plots whenever possible (use

matplotlib.animationorimageioto create gifs in Python); - if you have an important metric of interest (e.g. best accuracy) and you’ve already saturated your plot’s dimensions, print it somewhere on the plot rather than storing it in a separate file.

4. Keep different experiments in different scripts

This should probably go in the Code section of this post, but I’ll put it here as it relates more to experiments than to code.

Even with Rules 1 and 2 accounted for, sometimes you will have to make changes that are difficult to log.

In this case, I find it a lot more helpful to clone the current script (or create a new branch) and implement all variations on the new file.

This will prevent things like “"”temporarily””” hardcoding stuff to quickly test out a new idea, or having if statements in every other code block to account for the two different methodologies, and it will only add a bit of overhead to your development time.

The only downside of this rule is that sometimes you’ll find a bug or implement a cool plot in the new script, and then you’ll have to sync the old file with the new one. However, editors like PyCharm make it easy to keep files synced: just select the two scripts and hit ctrl + d to open the split-view editor which conveniently highlights the differences and lets you move the code around easily.

This is far from a complete guide (probably far from a guide at all), and i realize that some of the rules are not even related to working in teams. I just wanted to put together a small set of practices that I picked up from people way more skilled than me, in the hope of making collaborations easier, simplifying the workflow of other fellow PhD students that are just beginning to work with code seriously, and eventually, hopefully, leading to a more standardized way of publishing ML research in the sake of reproducibility and democratization.

I am sure that many people will know better, smarter, more common practices that I am unaware of, so please do contact me if you want to share some of your knowledge.

Cheers!